Rewilding

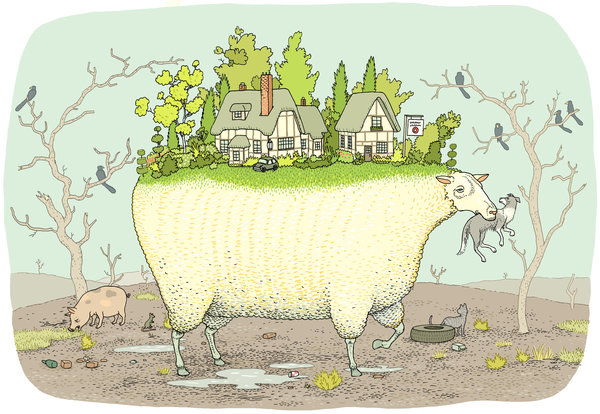

Pastoral Icon or Woolly Menace?

by Richard Coniff

You don’t have to look far to see the woolly influence of sheep on our cultural lives. They turn up as symbols of peace and a vaguely remembered pastoral way of life in our poetry, our art and our Christmas pageants. Wolves also rank high among our cultural icons, usually in connection with the words “big” and “bad.” And yet there is now a debate underway about substituting the wolf for the sheep on the (also iconic) green hills of Britain.

The British author and environmental polemicist George Monbiot has largely instigated the anti-sheep campaign, which builds on a broader “rewilding” movement to bring native species back to Europe. Until he recently relocated, Mr. Monbiot used to look up at the bare hills above his house in Machynlleth, Wales, and seethe at what Lord Tennyson lovingly called “the livelong bleat / Of the thick-fleeced sheep.” Because of overgrazing by sheep, he says, the deforested uplands, including a national park, looked “like the aftermath of a nuclear winter.”

“I have an unhealthy obsession with sheep,” Mr. Monbiot admits, in his book “Feral.” “I hate them.” In a chapter titled “Sheepwrecked,” he calls sheep a “white plague” and “a slow-burning ecological disaster, which has done more damage to the living systems of this country than either climate change or industrial pollution.”

The thought of all those sheep — more than 30 million nationwide — makes Mr. Monbiot a little crazy. But to be fair, sheep seem to lead us all beyond the realm of logic. The nibbled landscape that he denounces as “a bowling green with contours” is beloved by the British public. Visitors (including this writer, otherwise a wildlife advocate) tend to feel the same when they hike the hills and imagine they are still looking out on William Blake’s “green and pleasant land.” Even British conservationists, who routinely scold other countries for letting livestock graze in their national parks, somehow fail to notice that Britain’s national parks are overrun with sheep.

Mr. Monbiot detects “a kind of cultural cringe” that keeps people from criticizing sheep farming. (In part, he blames children’s books for clouding vulnerable minds with idyllic ideas about farming.) Sheep have “become a symbol of nationhood, an emblem almost as sacred as Agnus Dei, the Lamb of God,” he writes. Much of the nation tunes in ritually on Sunday nights to BBC television’s “Countryfile,” a show about rural issues, which he characterizes as an escapist modern counterpart to pastoral poetry. “If it were any keener on sheep,” he says, “it would be illegal.”

The many friends of British sheep have not yet called for burning Mr. Monbiot at the stake. But they have protested. “Without our uplands, we wouldn’t have a UK sheep industry,” Phil Bicknell, an economist for the National Farmers Union pointed out. “Farmgate sales of lamb are worth over £1bn” — or $1.7 billion — “to U.K. agriculture.” The only wolves he wanted to hear about were his own Wolverhampton Wanderers Football Club. A critic for The Guardian, where Mr. Monbiot contributes a column, linked the argument against sheep, rather unfairly, to anti-immigrant nativists, adding “sheep have been here a damn sight longer than Saxons.”

Mr. Monbiot acknowledges the antiquity of sheep-keeping in Britain. But the subjugation of the uplands by sheep, he says, only really got going around the 17th century, as the landlords enclosed the countryside, evicted poor farmers, and cleared away the forests from the hillsides and moorlands, particularly in Scotland. Britain is, he writes, inexplicably choosing “to preserve a 17th-century cataclysm.” The sheep wouldn’t be in the uplands at all, he adds, without annual taxpayer subsidies, which average £53,000 per farm in Wales.

He proposes an end to this artificial foundation for the “agricultural hegemony,” to be replaced by a more lucrative economy of walking and wildlife-based activities. He also argues for bringing wolves back to Britain, for reasons both scientific (“to reintroduce the complexity and trophic diversity in which our ecosystems are lacking”) and romantic (wolves are “inhabitants of the more passionate world against which we have locked our doors”). But he acknowledges that it would be foolish to force rewilding on the public. “If it happens, it should be done with the consent and active engagement of the people who live on and benefit from the land.”

Elsewhere in Europe, the sheep are in full bleating retreat, and the wolves are resurgent. Shepherds and small farmers are abandoning marginal land at an annual rate of roughly a million hectares, or nearly 4,000 square miles, according to Wouter Helmer, co-founder of the group Rewilding Europe. That’s half a Massachusetts every year left open for the recovery of native species.

Wolves returned to Germany around 1998, and they have been spotted recently in the border areas of Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark. In France, the sheep in a farming region just over two hours from Paris suffered at least 22 reported wolf attacks last year. But environmentalists there say farmers would do better protesting against dogs, which they say kill 100,000 sheep annually. Wolves are now a protected species across Europe, where their population quadrupled after the 1970s. Today an estimated 11,500 wolves roam there.

Lynx, golden jackals, European bison, moose, Alpine ibex and even wolverines have also rebounded, according to a recent study commissioned by Rewilding Europe. Mr. Helmer says his group aims to develop ecotourism on an African safari model, with former shepherds finding new employment as guides. That may sound naïve. But he sees rewilding as a realistic way to prosper as the European landscape develops along binary lines, with urbanized areas and intensive agriculture on one side and wildlife habitat with ecotourism on the other.

In northern Scotland, Paul Lister is working on an ecotourism scheme to bring back wolves and bears on his Alladale Wilderness Reserve, where he has already planted more than 800,000 native trees. He still needs government permission to keep predators on a proposed 50,000-acre fenced landscape. That’s a long way from introducing them to the wild, on the model of Yellowstone National Park. Even so, precedent suggests that it will be a battle.

Though beavers are neither big nor bad, a recent trial program to reintroduce them to the British countryside caused furious public protest. (One writer denounced “the emotion-based obsession with furry mammals of the whiskery type.”) And late last year, when five wolves escaped from the Colchester Zoo, authorities quickly shot two of them dead. A police helicopter was deployed to hunt and kill another, and a fourth was recaptured. Prudently, the fifth wolf slunk back into its cage, defeated.

Rewilding? At least for now, Britain once again stands alone (well, alone with its 30 million sheep) against the rising European tide.

The wolves of Chernobyl

Montana’s Glaciated Plains: Thinking Big Across Time and Space

Posted by Sean Gerrity of American Prairie Reserve, National Geographic Fellow on November 2, 2012

American Prairie Reserve’s mission to create a reserve of more than three million acres represents one of the largest conservation projects in the United States today. The size of the project is hard to grasp – even a small piece of the 274,000 acres that currently comprise the Reserve seems like an endless “sea of grass” to both first-time and seasoned visitors. However, after ten weeks of research on historical wildlife populations of Montana’s glaciated plains, I have become increasingly convinced that APR’s vision is necessary. If we want to understand the behavior and ecology of grassland species, we need to think big.

America’s iconic species – bison, pronghorn, elk, wolves, grizzly bears – evolved over tens of thousands of years on a wide-open continent. Over this long period of time, these species became well adapted to environmental “stochasticity,” the highly dynamic and unpredictable nature of their habitat. In fact, the prairie is one of the most dynamic ecosystems in the world.

Pronghorn race across the plains. Photo courtesy of Diane Hargreaves.

Settlers came to Montana in the early 20th century after being told that if they turned the soil they could transform the rugged landscape and cultivate a fertile Eden. A few years of unusually (and well-timed) wet conditions in the 1910′s bolstered this belief, but a severe drought in the 1920′s caused devastation for most agricultural producers. Unlike its settlers, though, the region’s wildlife had evolved several adaptations to deal with these rapid and extreme fluctuations. It turns out that the key to persistence in a highly stochastic environment is to employ a range of survival techniques.

On a wide-open continent, ungulates like elk, deer and pronghorn thrived in many different habitats and were able to chose from a toolkit of survival strategies grounded in their history and experience on the land. If conditions were optimal, herds would be inclined to stay put, but in periods of high environmental variance, they would have had to choose a new strategy. For instance, when temperatures dropped abnormally low, ungulates fled the prairie and sought thermal refuge in the Missouri River Breaks or the Rocky Mountains.

Elk in Autumn. Photo courtesy of Gib Myers/APR.

Through my research, I also discovered the debate over whether bison were historically a migratory or a nomadic species. Did they follow specific migratory patterns, or did they move in a sporadic, localized manner related to the availability of food? We’re not sure, but the truth is probably somewhere in the middle. Regardless, much of the migratory behavior that we observe in terrestrial species today is shaped by human intervention. We have severely restricted the habitats of most wildlife species, and climate change threatens what marginal areas remain.

Recent studies predict that changes in climate, such as increases in severe weather events and changes in precipitation levels, will affect grassland ecosystems, from native plant and weed distribution to altered fire regimes. Conservation planners will have to react to these to the best of their ability within the limits of science, funds, and space.

For the ungulate species that American Prairie Reserve (APR) is trying to recover, bigger is better. A large reserve would allow wildlife to utilize more of the strategies in their survival toolbox. It may also be able to buffer the adverse effects of climate change by encompassing more habitat niches and providing more space for wildlife to disperse while still remaining within reserve boundaries. Furthermore, a large area has the capacity to support higher numbers of wildlife, which greatly reduces the risk of a population extinction event.

Late afternoon light on the Reserve. Photo courtesy of Michelle Berry.

American Prairie Reserve recently celebrated the acquisition of a 150,000-acre property that more than doubled the size of previous habitat and added 16 miles of shared border with the 1.1 million-acre Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge. Even though the goal of APR seems very ambitious at times, we must remember that wildlife persisted on a much larger landscape for thousands of years before Lewis and Clark ever walked on this land.

Thus, it is a mistake to conceptually box these species into a specific habitat-type or set of behaviors. As Lewis put it, the historical American West contained “immence herds of Buffaloe, Elk, deer and antelopes feeding in one common and boundless pasture.” While we will never be able to recapture the full picture of historical wildlife on the frontier, American Prairie Reserve can reestablish a pretty big chunk of that natural legacy.

American Prairie Reserve intern Michelle Berry is a Master’s student in environmental studies at Stanford. She has been tasked with examining historical works of literature and other primary sources to establish wildlife population estimates in the Reserve region of northeastern Montana.Her 10-week internship was made possible by the Bill Lane Center for the American West.

Source: http://newswatch.nationalgeographic.com/2012/11/02/montanas-glaciated-plains-thinking-big-across-time-and-space/

Why Wolves? – David Parsons

Dave Parsons, TRI’s Carnivore Conservation Biologist, gave a lecture in Santa Fe for a program called Science Cafe for Young Thinkers sponsored by the Santa Fe Alliance for Science. The lecture is about wolf ecology and trophic cascades explained at a high school level.

George Monbiot: For more wonder, rewild the world

Ghosts of the Appalachians or the Missing Actors?

When we pass through the Appalachian Mountains along its vast extent from the humid southeast of Alabama and Georgia to the cold and barren of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, we cannot help but marvel of its beauty and extensiveness. Unlike its western cousin, the Rocky Mountains, which is a mixture of forested ranges imbedded in a matrix of lowland shrub and grass ecosystems, the Appalachians are heavily forested mountains imbedded in what is likely one of the largest forest ecosystems in the world. One can only imagine the extensiveness of the original eastern forest, extending to the north as far as the tundra, to the south to the Gulf of Mexico and to the west until the beginning of the Great Plains. It is this eastern “endless” forest that provided the opportunities and resources to the Earlier Americans who lived there for centuries. It is also this bountiful forest that gave the European explorers who followed their toehold on the continent. Rich in plant and wildlife resources, the eastern forest likely had one of the highest densities of Earlier Americans in North America. Even today, the eastern forest continues to support the highest density of Current Americans.

Much has been written about the destruction of the eastern forests by early European colonists and their descendants. However, today past abuses and scars of these earlier settlers have been covered over by an extensive mantel of young and thriving forest mixed in with verdant farmland. In fact, the structure of the current forest ecosystem of the east is probably much like that before Europeans arrived, a mixture of open farmland and dense forest. Today, as in those earlier times, the open farmland provides areas of high productivity where many species of wildlife can find food while the forest provides shelter from the elements.

To the viewer’s eye, it would seem that the eastern forests, especially the Appalachian Mountains, have returned to much of their former beauty and glory. Even in the more populated areas of the East, the forest extends its fingers into the fringes of the cities. It is only in the East that abandoned land quickly reverts to forest! In these extensive forests all along the eastern seaboard, abundant wildlife, small song birds and mammals, larger turkeys, hawks, and even larger deer and bear, are again abundant in many parts of the Appalachian chain. Though much was lost in the past, the recuperation of the eastern forest ecosystem throughout the eastern seaboard makes it a true success story, a paradise gained! All this in light of one of the highest human densities in North America!

But has the Eastern Forest truly returned to its past glory as an ecosystem? An ecosystem is not like a museum, not just a static collection of parts, plants and animals. It is a dynamic entity, one that constantly changes, grows, dies. All its parts have a function, a function vital to the health of the ecosystem. The plants of an ecosystem function as extensive solar traps, each day, month, year, capturing immense amounts of solar energy. That energy is transferred along to other parts of the ecosystem in a cascading chain of actions reaching the smallest corners, maintaining the diversity of life found there. In each step, energy is transferred, energy is lost. Eventually that energy passes out of the ecosystem, replaced by new waves of solar radiation. In a true sense, the function of an ecosystem is this transfer of solar energy from one component to the next. It is this energy transfer that keeps the ecosystem “alive”, maintaining its integrity and its diversity.

My manifesto for rewilding the world

Nature swiftly responds when we stop trying to control it. This is our big chance to reverse man’s terrible destructive impact

Could the destruction of the natural world be reversed? Could our bare hills once more support a rich and thriving ecosystem, containing wolves, lynx, moose, bison, wolverines and boar? Does our wildlife still bear the marks of the great beasts that once roamed here? George Monbiot narrates an animation on the enchanting subject of rewilding.

Until modern humans arrived, every continent except Antarctica possessed a megafauna. In the Americas, alongside mastodons, mammoths, four-tusked and spiral-tusked elephants, there was a beaver the size of a black bear: eight feet from nose to tail. There were giant bison weighing two tonnes, which carried horns seven feet across.

The short-faced bear stood 13ft in its hind socks. One hypothesis maintains that its astonishing size and shocking armoury of teeth and claws are the hallmarks of a specialist scavenger: it specialised in driving giant lions and sabretooth cats off their prey. The Argentine roc (Argentavis magnificens) had a wingspan of 26ft. Sabretooth salmon nine feet long migrated up Pacific coast rivers.

During the previous interglacial period, Britain and Europe contained much of the megafauna we now associate with the tropics: forest elephants, rhinos, hippos, lions and hyenas. The elephants, rhinos and hippos were driven into southern Europe by the ice, then exterminated about 40,000 years ago when modern humans arrived. Lions and hyenas persisted: lions hunted reindeer across the frozen wastes of Britain until 11,000 years ago. The distribution of these animals has little to do with temperature: only where they co-evolved with humans and learned to fear them did they survive.

Most of the deciduous trees in Europe can resprout wherever the trunk is broken. They can survive the extreme punishment – hacking, splitting, trampling – inflicted when a hedge is laid. Understorey trees such as holly, box and yew have much tougher roots and branches than canopy trees, despite carrying less weight. Our trees, in other words, bear strong signs of adaptation to elephants. Blackthorn, which possesses very long spines, seems over-engineered to deter browsing by deer; but not, perhaps, rhinoceros.

All this has been forgotten, even by professional ecologists. Read any paper on elephants and trees in east Africa and it will tell you that many species have adapted to “hedge” in response to elephant attack. Yet, during a three-day literature search in the Bodleian library, all I could find on elephant adaptation in Europe was a throwaway sentence in one scientific paper. The elephant in the forest is the elephant in the room: the huge and obvious fact that everyone has overlooked.

Since then much of Europe, especially Britain, has lost most of its mesofauna as well: bison, moose, boar, wolf, bear, lynx, wolverine – even, in most parts, wildcat, beavers and capercaillie. These losses, paradoxically, have often been locked in by conservation policy.

Conservation sites must be maintained in what is called “favourable condition”, which means the condition in which they were found when they were designated. More often than not this is a state of extreme depletion, the merest scraping of what was once a vibrant and dynamic ecosystem. The ecological disasters we call nature reserves are often kept in this depleted state through intense intervention: cutting and burning any trees that return; grazing by domestic animals at greater densities and for longer periods than would ever be found in nature. The conservation ethos is neatly summarised in the forester Ritchie Tassell’s sarcastic question, “how did nature cope before we came along?”

Through rewilding – the mass restoration of ecosystems – I see an opportunity to reverse the destruction of the natural world. Researching my book Feral, I came across rewilding programmes in several parts of Europe, including some (such as Trees for Life in Scotland and theWales Wild Land Foundation) in the UK, which are beginning to show how swiftly nature responds when we stop trying to control it. Rewilding, in my view, should involve reintroducing missing animals and plants, taking down the fences, blocking the drainage ditches, culling a few particularly invasive exotic species but otherwise standing back. It’s about abandoning the biblical doctrine of dominion which has governed our relationship with the natural world.

The only thing preventing a faster rewilding in the EU is public money.Farming is sustained on infertile land (by and large, the uplands) through taxpayers’ munificence. Without our help, almost all hill farming would cease immediately. I’m not calling for that, but I do think it’s time the farm subsidy system stopped forcing farmers to destroy wildlife. At the moment, to claim their single farm payments, farmers must prevent “the encroachment of unwanted vegetation on agricultural land”. They don’t have to produce anything: they merely have to keep the land in “agricultural condition”, which means bare.

I propose two changes to the subsidy regime. The first is to cap the amount of land for which farmers can claim money at 100 hectares (250 acres). It’s outrageous that the biggest farmers harvest millions every year from much poorer taxpayers, by dint of possessing so much land. A cap would give small farmers an advantage over large. The second is to remove the agricultural condition rule.

The effect of these changes would be to ensure that hill farmers with a powerful attachment to the land and its culture, language and traditions would still farm (and continue to reduce their income by keeping loss-making sheep and cattle). Absentee ranchers who are in it only for the subsidies would find that they were better off taking the money and allowing the land to rewild.

Despite the best efforts of governments, farmers and conservationists, nature is already starting to return. One estimate suggests that two thirds of the previously forested parts of the US have reforested, as farming and logging have retreated, especially from the eastern half of the country.

Another proposes that by 2030 farmers on the European continent (though not in Britain, where no major shift is expected) will vacate around 75m acres, roughly the size of Poland. While the mesofauna is already beginning to spread back across Europe, land areas of this size could perhaps permit the reintroduction of some of our lost megafauna. Why should Europe not have a Serengeti or two?

Above all, rewilding offers a positive environmentalism. Environmentalists have long known what they are against; now we can explain what we are for. It introduces hope where hope seemed absent. It offers us a chance to replace our silent spring with a raucous summer.

Coin event – Launch of George Monbiot’s book ‘Feral’ about rewilding and climate change. from Zoe Broughton on Vimeo.

• A fully referenced version of this article can be found at monbiot.com

Sources:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/may/27/my-manifesto-rewilding-world